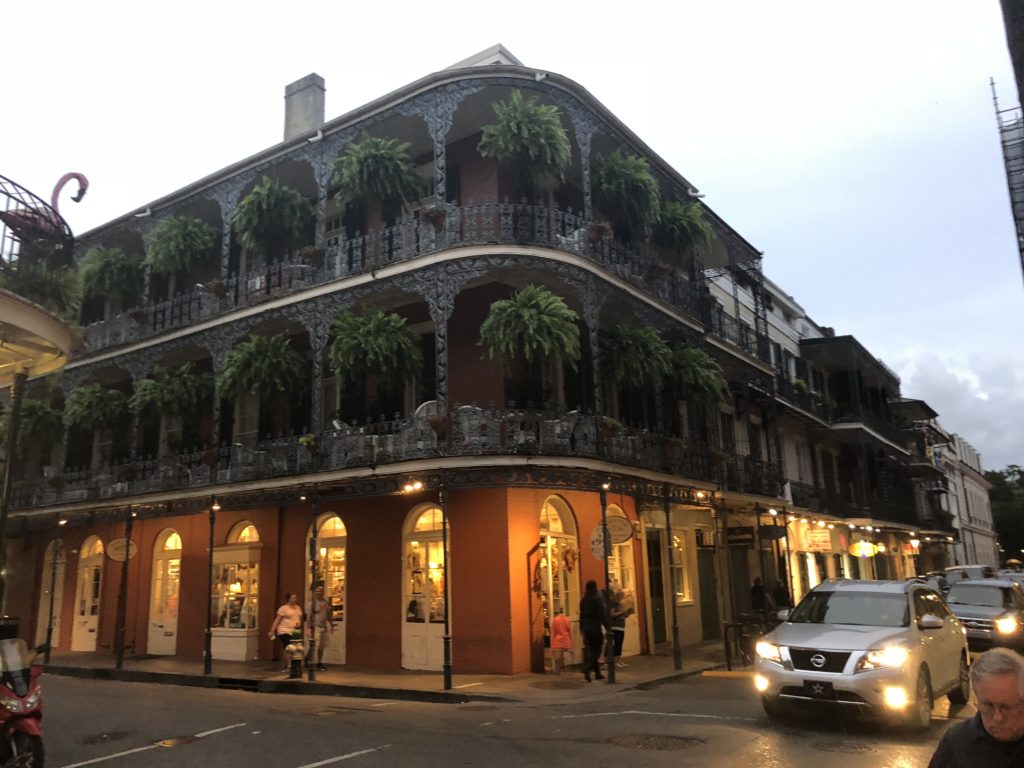

New Orleans was founded by the French in 1718 and became the capital of the massive French territory of Louisiana. Situated near the mouth of the enormous and navigable Mississippi River, the city became a key port that linked the entire territory (much of the continent) to the ocean. After the Brits beat the French in the Seven Years War, the colony was ceded to Spain. Under the Spanish, the city built much of its distinctive 18th century architecture that still wows people today. This is most prominent in the French Quarter (Vieux Carre), take a look:

The heart of the French Quarter is Jackson Square (originally: Place d’Armes). At its centre is a large statue of Andrew Jackson, a general during the historic 1815 Battle of New Orleans that secured American supremacy over the continent. Jackson went on to become the 7th president of the United States. Behind the square is the impressive St Louis Cathedral, the country’s oldest and surely one of its grandest. The city’s French and Spanish roots ensure that Catholicism has a strong presence.

Next to the Cathedral is The Cabildo, which was once the seat of the Spanish colonial government. The grand building now houses a pretty good museum of the city.

New Orleans and the Louisiana territory briefly reverted to French rule before Napoleon sold the whole lot to the United States in 1803 for $15 million. This effectively doubled the fledgling nation’s size. Around this time, the city was flourishing, and became a haunt of smugglers, gamblers, prostitutes and pirates. Over the next hundred years with continued expansion and trade, New Orleans became an economic powerhouse – the biggest city in the South and the third biggest in the country.

The city’s status has waned over the last hundred years as the North industrialised and other Southern cities gained prominence. But New Orleans retains a large and crucial port, the fifth largest in the country by bulk tonnage (lower ranking by value). In addition, a 90km stretch of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge is home to the sprawling Port of South Louisiana – the largest in the country by tonnage including 60% of all grain exports (mostly coming from the Midwest). Logistics, oil & gas, and tourism are now the cornerstones of the New Orleans’ economy.

Streetcars are synonymous with New Orleans. The form of public transportation dates all the way back to the 1830’s. The city has retained five streetcar lines, including the St. Charles Line, the oldest continuously operating streetcar line in the world. Each car on that specific line is an historic landmark and about 100 years old. We decided to have a closer look.

The route runs along St. Charles Avenue (a.k.a. “The Avenue”) through some of the most beautiful parts of the city.

Slavery in New Orleans was as old as the city itself, and it developed into a major slave market that fed the demand in its ports and on surrounding sugar plantations. A large population of free African Americans developed over time, including immigrants and refugees from the American revolution, the French revolution, and revolts in Saint-Domingue (Haiti). Over time, the city’s population mixed and developed a distinctive “Creole culture”.

The term “Creole” derived from a Spanish word and originally defined anyone born in the Louisiana region – i.e. native to that area as opposed to having immigrated from France or Spain. The term included native-born, French-speaking slaves. Today, the term now includes anyone or anything native to Louisiana, and in particular, its African American population.

As a true melting pot of peoples and cultures, its no surprise that New Orleans’ food is varied, delicious, and known across the world. During our stay we sampled a few of the highlights including Creole classics like jambalaya and gumbo, French beignets (“ben-yays”; French doughnuts), Italian muffuletta sandwiches. and praline confectioneries.

Many claim that New Orleans gave birth to ‘jazz’ music. A whole range of factors blended together to make this possible – the city had a more relaxed and tolerant attitude; it had a long marching band tradition and developed a tradition of public celebration that embraced music and dance; the city saw waves of immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, part of America and Europe, ensuring a mix of musical styles. Perhaps it is simplest to say that New Orleans music was born out of European instruments and African rhythms.

Various forms of music – blues, brass bands, church and classical music – melded together and at the same time became more loose, playful and experimental. Performers began “ragging” or syncopating well known parts of songs. Improvisation became key as front line players (on cornet, clarinet, or trombone) began interweaving two or three melodies in distinctive ways. Musicians learned to play off each other spontaneously and move towards collective improvisation. It was live, upbeat, dance-inspiring “hot jazz”, and bands competed against each other in “cutting contests”.

Jazz really took off in the 1920’s. Postwar America was booming and became more casual and less inhibited. The pulsing and ragged rhythms spoke to the youth of the time, just like rock music would do a few decades later. Many big-name New Orleans performers made the move up to Chicago and New York, which offered looser racial laws and bigger shows. A brilliant young cornetist, Louis Armstrong, made such a move in 1922, and his band, the Hot Five, became a big hit. The late 1920’s saw jazz in its golden age. Over the subsequent decades, jazz shifted from collective improvisation to focusing on the improvising soloist, and steadily moved from dance floors to smaller clubs & halls.

Today, jazz is alive and well in New Orleans. Around every corner in the French Quarter, we heard a different band playing a different sound. It was an absolute pleasure popping into various bars and venues on a whim to catch high-quality performances during our stay. It felt like the city was pulsing with rhythm and magnetic energy.

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina formed in the Atlantic Ocean, passed over Florida, and grew in size and strength over the unusually warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico – climbing from a Category 3 to a Category 5 hurricane in the process (different categories represent the maximum sustained wind speeds, with a Category 5 in excess of 250 km per hour). From there, Katrina shifted northwards on a collision course with the Louisiana & Mississippi coastlines. It became clear that New Orleans was in the storm’s path, and the first-ever mandatory evacuation of the city was called. The next day, 29 August 2005, Katrina struck.

The interesting thing about New Orleans is that it is mostly situated below sea level. In the 20th century, the city implemented a novel drainage system that turned the swamps that encircled the city into usable land, allowing the population to expand. This already low-lying land began to subside (sink) incrementally over time – a process that continues today. In the past, the city has seen its fair share of Mississippi floods and Hurricane strikes. Thus, along the river that cuts through the south side of the city, New Orleans has earthen river banks topped with steel and concrete floodwalls that add 23 feet of flood protection. To the north, a similar arrangement provides over 17 feet of flood protection from Lake Pontchartrain. Collectively, these are the city’s “levies”, and are overseen by the federal government.

Katrina actually approached the coast a little to the east of New Orleans. On approach, the exceptionally powerful winds pushed water from the Gulf into Lake Pontchartrain (north of the city). Then, as Katrina made landfall and continued moving northwards, the anti-clockwise spin of the hurricane meant that powerful winds now pushed that amassed water directly into New Orleans’ northern floodwalls. The flood surge overwhelmed these defenses, including key levies at the 17th Street Canal, London Avenue Canal, and the Industrial Canal. In all, water breached the levies in 53 spots submerging 80% of the city and leading to well over a thousand deaths. Total damage tallied $125 billion, making Katrina both the deadliest and the most costly hurricane in US history.

It was later established that breaches of the levies were primarily due to system design and construction flaws (e.g. steel sheet pilings needed to be twice as deep). Many subsequent events made matters worse. The city has enormous pumps that help remove water from the city. Ironically, these were inundated with flood water which overwhelmed the pump’s power systems. Had these been in operation (with, for example, the power systems encased or elevated), the city may have been drained within a day. Instead, water sat there for weeks. A key bridge over Lake Pontchartrain collapsed, again with poor design partially to blame, which hindered relief efforts. Stranded residents went to the city’s huge football stadium (Louisiana Superdome) for emergency shelter, and that too had many problems. Katrina was an epic disaster. The city’s population was still half of its original level two years later, before rebounding.

We stayed at an Airbnb in the city, located close to the London Avenue Canal. In 2005, the property was completely devastated by the flood. The rebuild, however, was quite impressive – note the elevated position:

A few more pictures of “N’awlins”:

For us, the Big Easy was everything it is cracked up to be – a ‘must-see’ city. The world famous Mardi Gras celebration is in late February which is perhaps something to aim for on a return visit. Onwards to Alabama…