We drove the scenic 54-mile stretch of the US-80, westward from Montgomery to Selma. Along this exact route (in the reverse direction) in late March 1965, hundreds of protesters made the historic march to demand enforcement of their right to vote. By the time they reached the state capital of Montgomery, the march had swelled to 25,000 strong.

Selma was settled in 1815, and over the years became a regional trading centre with a focus on cotton. By the time of the Civil War, the town had a major iron works & foundry that produced weapons & even ships, making it a key target for the Union Army. The northerners routed the Confederates in the Battle of Selma in 1865. In the decades following the Civil War and “Reconstruction”, Jim Crow laws ensured segregation & the disenfranchisement of African Americans via poll taxes, literacy tests, intimidation and violence. In 1950, African Americans were half of the voting age population, yet only 1% were registered to vote.

The Dallas County Voters League was formed to help more people register to vote. This attracted larger groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC; headed by Martin Luther King Jr.). As was common at the time, such organisation took place in churchs and was lead by ministers, in this case the Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Selma. Local laws in the South often prohibited African Americans from gathering in large groups except in their churches. Meanwhile, preachers had the moral authority of their positions plus they were beholden only to their congregation (others faced economic reprisal for protest actions). Brown Chapel became the staging point for various groups to march to the nearby Dallas County Courthouse to register to vote. They were either ignored or arrested.

In early March 1965, following the death of a protester at the hands of state troopers, 600 marchers left Brown Chapel on a memorial march headed for the state capital of Montgomery, 54 miles away. A few minutes later, on their way out of town, they started to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River. As they reached the apex of the bridge, they saw a sea of blue on the other side – Alabama state troopers blocking the US-80. Marchers, led by John Lewis (SNCC) and Hosea Williams (SCLC), stopped short of the troopers but did not turn back when ordered. State troopers fired tear gas and charged the protesters, beating them with nightsticks as they fled. That day became “Bloody Sunday” and was all recorded and widely distributed by major news media, showing the country and the world what was happening in the South.

A few days later, a second march of 2,000 from Brown Chapel reached the same spot, kneeled to pray, and then turned around – a court order limited any further activity. A week later, President Johnson called on Congress to pass a voting rights bill that would override Jim Crow-type local laws. On 21st March 1965, a third more-jubilant march of 4,000 set off from Brown Chapel, over the Edward Pettus Bridge and towards US-80, this time unencumbered by state troopers. President Johnson had sent American troops (and even federalised the Alabama national guard) to line the route as protection. Over four days and 54 miles, a smaller group of 300 marchers (the numbers were legally restricted due to the size of the highway) made their way from Selma to Montgomery. As they approached the state capital, their numbers swelled to 25,000.

The enormous crowd reached the foot of the steps leading up to the Capitol building. A delegation of protesters tried to meet with Alabama governor George Wallace to give him a petition to ask for an end to racial discrimination in the state. They were not allowed to see him. A passage of the petition read: “We have come not only five days and fifty miles by we have come from three centuries of suffering and hardship. We come to you, the Governor of Alabama, to declare that we must have our freedom now. We must have the right to vote; we must have equal protection of the law and an end to police brutality”. Martin Luther King Jr. gave a historic speech from the back of a flatbed truck parked at the base of the Capitol steps, saying that “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice”. A stone’s throw away was the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church where he ministered around the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott ten years prior. A lot had changed in a decade.

On 6th August 1965, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, suspending literacy tests, challenging poll taxes, and appointing federal election monitors – actions to enforce the ratified 15th Amendment that gave all citizens the right to vote. The nonviolent Civil Rights Movement, of which Selma and Montgomery were an important part, was incredibly effective.

Selma is a historic place. The Selma Interpretive Center is a museum close to the Edmund Pettus bridge that does a great job of explaining events surrounding the marches of Selma, which were extensively covered in news media. Some of the footage is very real and disturbing, but ultimately, hopeful. You can find plenty of actual footage from Selma on Youtube, like this one:

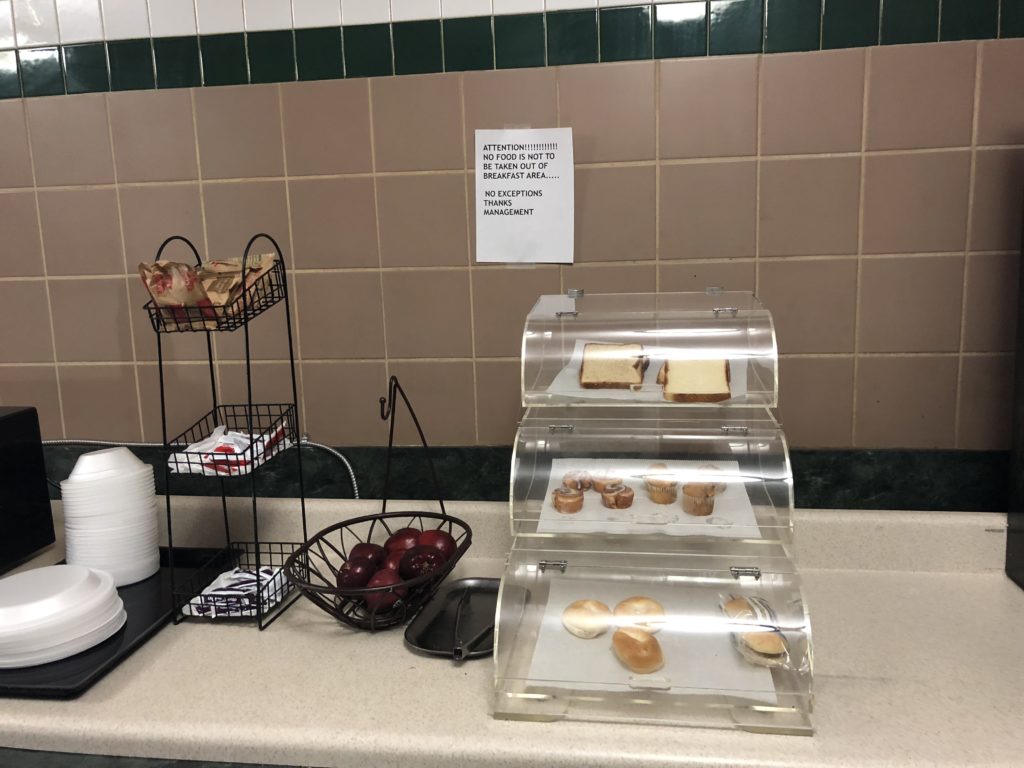

While we had a highly memorable time exploring historic Selma, our accommodation there may have been the worst of our entire North American trip. A last minute booking meant only a handful of motels on offer, and I think we may have chosen the worst of the lot. The rooms were rough; the well-advertised swimming pool was and smelt like a cesspool; at one point in the night police cars showed up to investigate an altercation of some kind in the complex; and the morning’s breakfast was the opposite of appetising. Ella still has nightmares. Pick wisely when choosing accommodation here.

The Selma Times-Journal, the local weekly newspaper, apparently has a fairly good long-term track record of balanced reporting over the decades – very local news with a decent opinions section. Family Dollar and Winn Dixie fighting it out for grocery dollars.

From Selma, we set off west and northwards towards Mississippi. Here are a few pictures of western Alabama as we made our way out of the state.

Off to mighty Mississippi – the home of both delta blues & the king of rock ‘n roll.