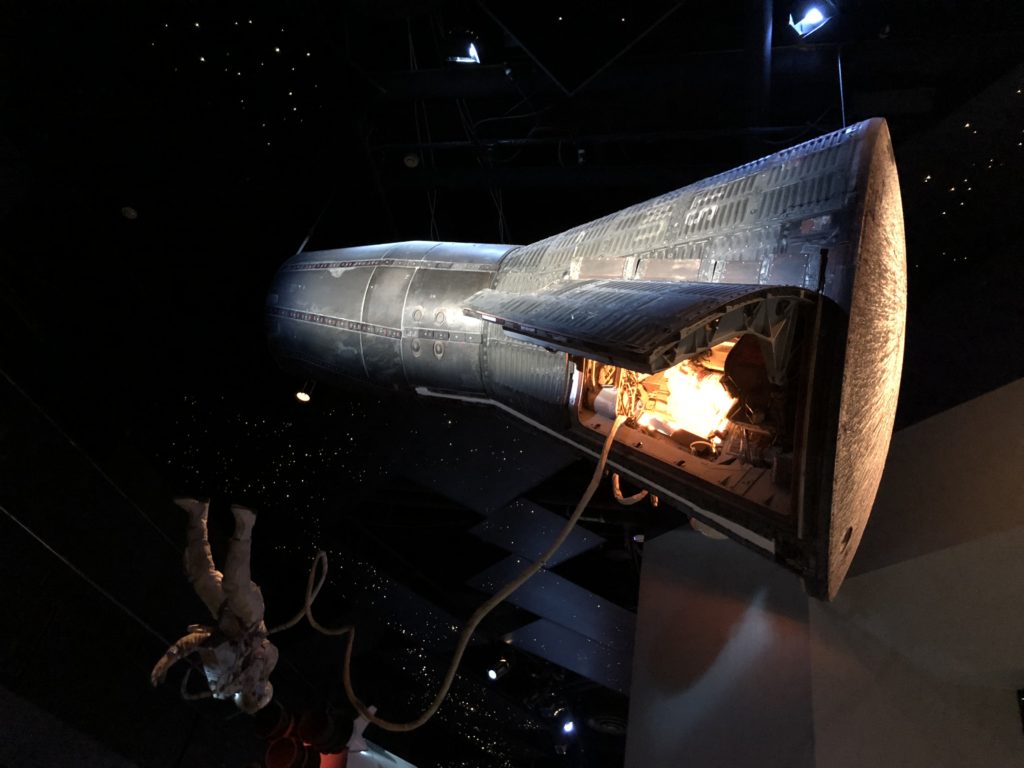

In 1957, the Russians shocked the world by putting Sputnik 1 into orbit, the first man-made satellite in space. This jolted the Americans into action, leading to the formation of NASA and Project Mercury. The goal: put a man into space (>100km above the earth) and return him safely. The program achieved this goal in 1961, three weeks after the Russians did. Over its six-year span, Project Mercury launched twenty “uncrewed” flights (successes & failures) and six one-man flights, which all ended in success. The longest of these missions was about a day and a half, resulting in 22 orbits and a maximum height of nearly 300km above the earth.

The next step was to put two astronauts into space – Project Gemini – and plans were already being laid for three-man flights under the ‘Apollo’ program, with sights set on the moon. President Kennedy laid down this gauntlet in a speech in May 1961. NASA had outgrown its existing facilities, and began looking for a new home for its manned space programs. A huge stretch of grazing land, 40km southeast of Houston, was selected and in 1963 the Manned Spacecraft Center was opened. Since then, “Houston” has been at the heart of America’s space activities, home to astronaut training & the critical role of Mission Control. The site was renamed the “Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center” in 1973, and today is home to over 100 buildings and 3,200 staff.

We arrived at the visitor center (“Space Center Houston”), adjacent to the huge Johnson Space Center complex, quite early in the morning. The first thing you see is an replica of a Space Shuttle on top of a genuine Boeing 747 Shuttle Carrier called NASA 905. NASA 905 hauled shuttles on 220 occasions over 42 years before retiring. The scale is hard to capture. The two aircraft house mini-museums inside, both with interesting displays.

Next, we hopped on the open-air tram tour of the Johnson Space Center. The first stop was Building 30, the “Mission Control Center”. Over the history of America’s space efforts, most launches took place all the way over in Cape Canaveral, Florida. The reasons: (1) can launch eastwards over the ocean and not over populated areas, (2) it’s near the equator where the earth is moving west-to-east at its fastest pace. After launch, however, this Mission Control Center takes the reigns. Building 30 has performed this mission control function since the fourth Gemini mission, through all the Apollo and Shuttle missions, right until today.

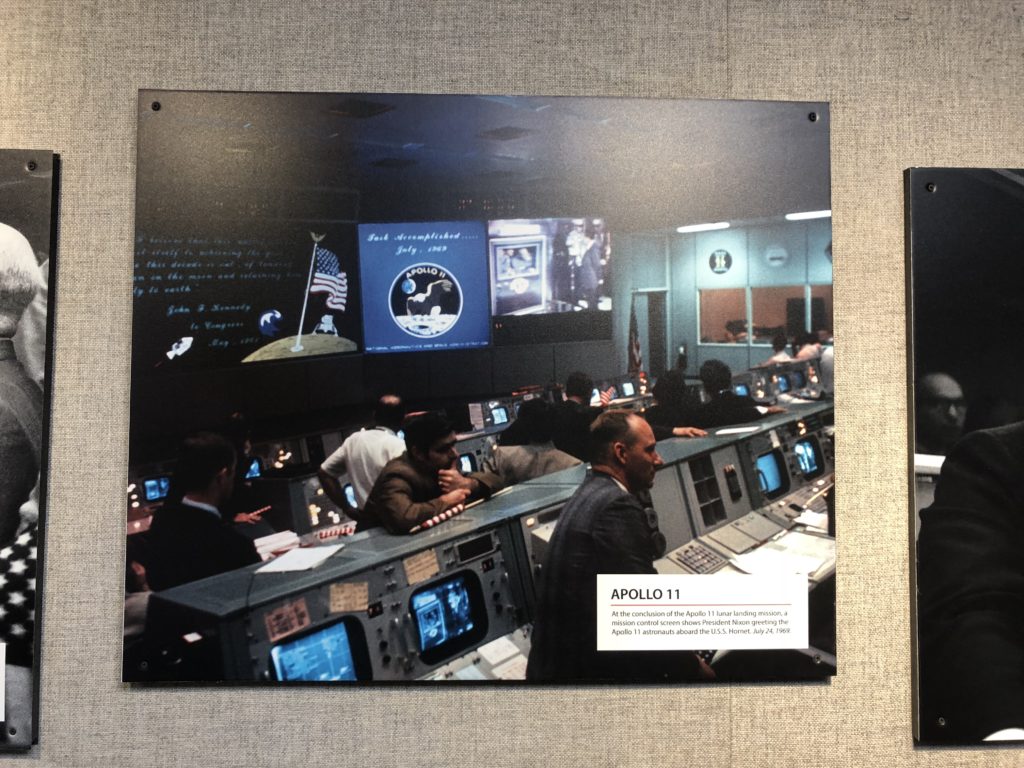

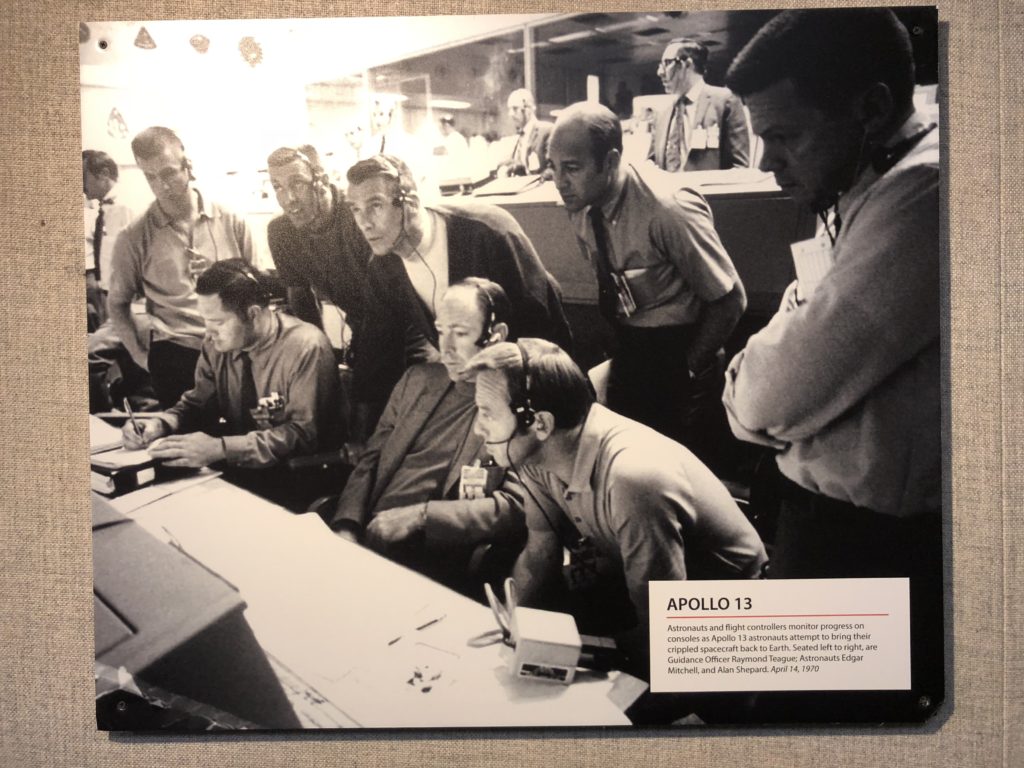

Mission Operations Control Room 2 is now a National Historic Landmark within Building 30. It was unfortunately going through extensive renovation to make it look like it once did in the 1960s. Nevertheless, it was an incredible feeling to look into the very room where NASA witnessed Armstrong’s first steps, guided the Apollo 13 craft back to earth in one piece, and monitored Space Shuttle missions for decades. These momentous events obviously have to happen somewhere, but seeing THE place was quite something. There must have been plenty of jubilant, anxious, and sombre moments in this room over the years. In its prime, it was probably one of the most high-tech places on earth. Building 30 is still NASA’s Mission Control Center, but this all takes place in a new wing that is not usually open to visitors. Current missions include the US operations at the International Space Station, upcoming Artemis flights and possibly trips to Mars.

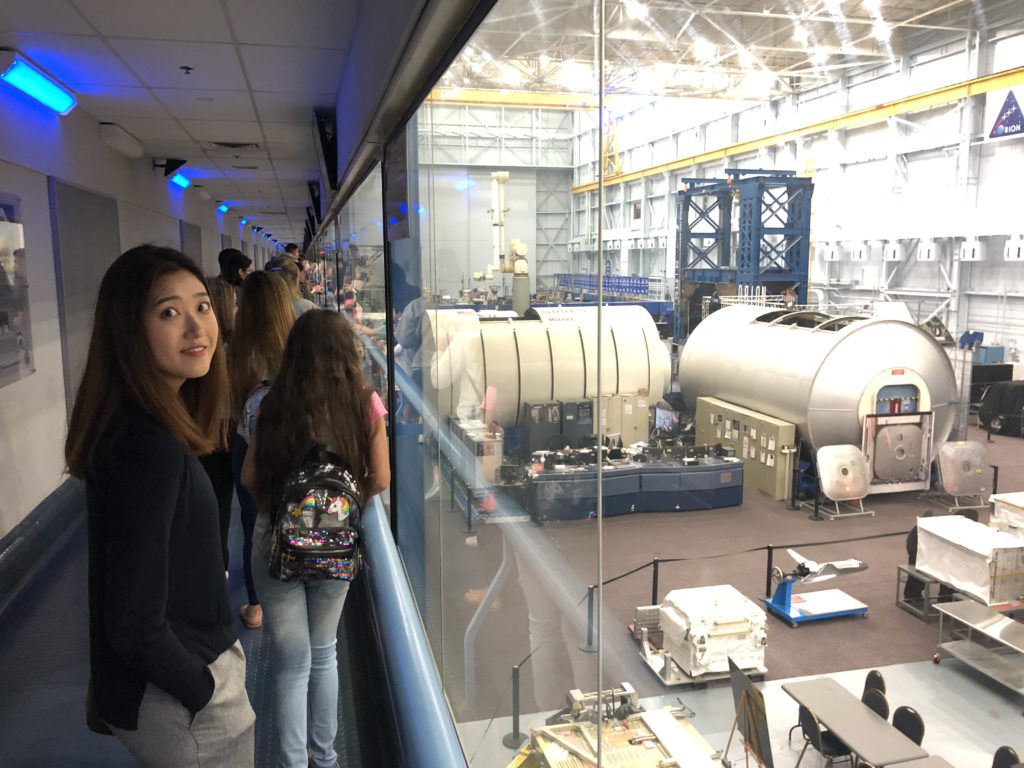

The next stop on the tram tour was building 9, the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility. Here, astronauts train for missions and engineers develop all sorts of space facilities and exploration vehicles.

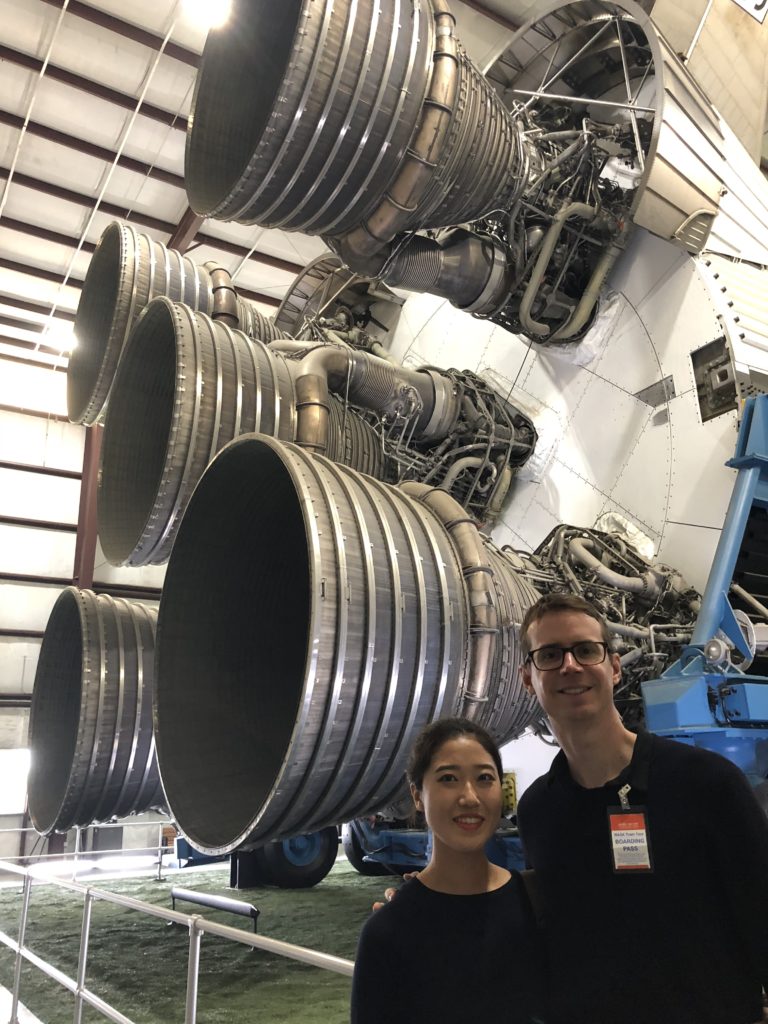

The final stop on the tram tour was “Rocket Park”, where they have an original Saturn V rocket on display. The Saturn V remains the most powerful rocket ever flown, and was mostly used during the Apollo program to get astronauts to the moon. Saturn Vs stand 110 metres tall, and were used 13 times with no failures. About fifty years later, SpaceX’s Starship / Super Heavy may finally eclipse the Saturn V in terms of power. The Saturn V on display is made up of different pieces (called stages) intended for use in missions that never materialised. Up close, it’s a beast.

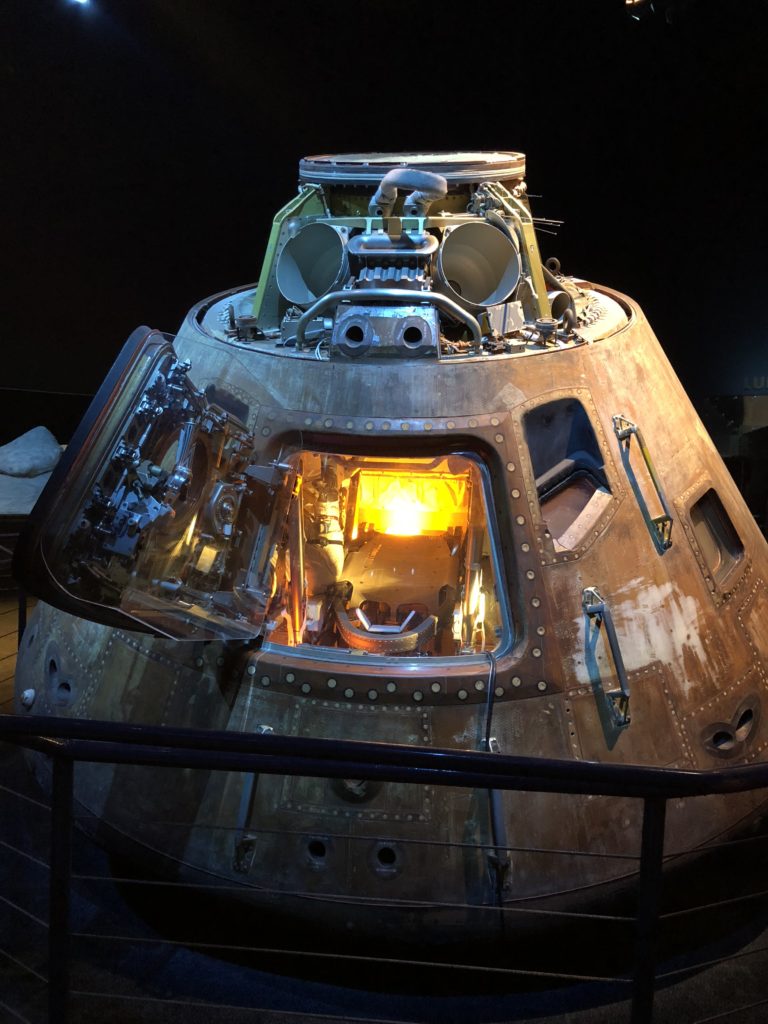

The Saturn V rocket was made up of three stages with the Apollo spacecraft on top. The first stage would blast for a little under three minutes, taking the rocket about 68km above the earth, after which it would detach and be discarded into the ocean. The second stage would then take over and fire for less than 10 minutes, boosting the craft into space. This stage would detach and burn up in the atmosphere. The third stage would then fire for about three hours and get the remaining craft on its way to the moon. At some point, the Apollo spacecraft would detach from the rocket and retrieve the lunar lander from within third stage, before continuing on its own way to the moon. Incredible.

The rest of the day was spent in the visitors center. They offer a number of interesting films, some talks about life in space, and various exhibits about past space travel or future plans. You could easily spend a whole day here – it is full of interesting and historic stuff.

The idea of space travel is simply fascinating – the last frontier, the wonder of pure exploration, venturing into unknown worlds. After going through a lengthy funk, the future of space travel seems to have brightened considerably over the last decade – including the possibility of tourist space flights, missions to the moon, and maybe even Mars. Perhaps we are entering a new phase of human space travel, one that may see as much progress as was experienced in the 1960s. It is incredibly exciting and a great time to be alive.