After a fantastic time in the big city of Melbourne, we decided to do as the Melburnians do: road trip the Great Ocean Road, a 240km highway along the southern coast of Victoria. It connects a number of small coastal communities and was built right after WWI by returning servicemen. Interestingly, it’s known as the world’s largest war memorial. The Great Ocean Road is shaped like a “V”, the downward sloping right-hand section goes from Torquay to Cape Otway and is called Surf Coast, while the upward sloping left-hand section ends near Warnambool and is called Shipwreck Coast. Midway up this second section, we kicked off our west-to-east week-long meander in the small town of Port Campbell (pop. 500).

The attraction here is the incredible coastline: the soft limestone rock in the ground, under constant bombardment from relentless waves fueled by arctic winds, has steadily eroded and receded over time, leaving behind dramatic cliffs punctuated with giant rock pillars and arches – an awesome landscape. It’s a highly tangible display of the unstoppable force of nature as big waves simply smash into rock cliffs, with each roaring crash the “sound of inevitability”. One can’t help but feel small. At an estimated 2cm a year, the tireless ocean advance continues day in, day out.

The biggest drawcard here is the Twelve Apostles, a series of big rock pillars standing defiantly in the surf – the last survivors of what was once a wall of rock. While resistance is surely futile, they do look glorious in their defiance. The scale is impressive too, with some towering over 50m tall. Interestingly, when the area was named, there weren’t twelve pillars, but eight – good marketing needn’t be bound by facts. The number reduced further after one collapsed in 2005. At some point in time I suppose there must have been twelve…

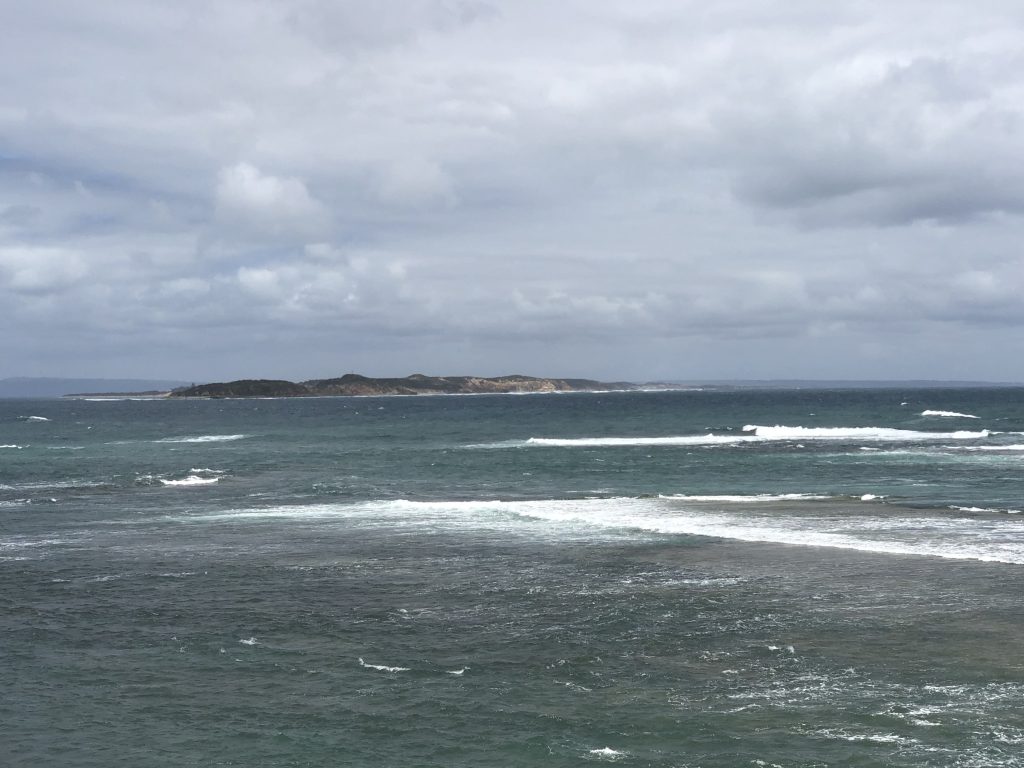

As mentioned, this part of the Great Ocean Road is nicknamed Shipwreck Coast. It was the final stretch of the three-month naval journey from England to Melbourne, and ships were required to “thread the needle” through the 90km gap between this coast and King island (or add a 5-day trip around Tasmania). With rudimentary 19th century navigation technology, many a ship lost its bearings. There are estimated to have been as many as 638 shipwrecks in the area, of which 240 have been discovered thus far. One of the most famous is that of the Loch Ard in 1878. Right at the end of its three-month journey, in a thick pre-dawn fog, the Loch Ard smashed into the rocky shore and sank. The ship’s apprentice, Tom Pearce, was swept ashore through a narrow opening in the rocks into a sandy gorge. Upon hearing cries for help he managed to swim out and rescue another: 18 year-old Eva Carmichael, an Irish immigrant. The other 52 passengers and crew all perished. The two teenagers made it out of the gorge and on to Melbourne. The gorge became the Loch Ard Gorge.

We journeyed on along the coast, passing forested hills and glorious seascapes. Right at the bottom of the Great Ocean Road’s “V”-shape, we arrived at Cape Otway, home to an old lighthouse with a view. In the late 1800’s, from its lantern room, a bright light (21 lamps and reflecting panels) fueled with whale oil reached out almost 50km into the ocean, announcing to all who sailed nearby: “Here be land”. To passengers at the tail-end of a 2~3 month voyage, perhaps it called out “Welcome to Australia”. In the 1890’s, the fuel was upgraded to kerosene and an iconic Fresnel lens was added. Today, the Cape Otway Lighthouse is enjoying its retirement, as a nearby solar-powered modern light beacon fulfills its original duties (not to mention modern GPS navigation). Nevertheless the sleepless watchman still looks grand.

A large portion of Cape Otway itself is a national park, and its known to be home to plenty of koalas. We scanned and scanned the tree tops as we drove along without any luck, until we arrived in the nearby town of Marengo, where a furry fella was waiting for us right outside our Airbnb.

Our next stop was just around the corner: Apollo Bay, which really hit the spot – a small holiday town with broad white-sand beaches, some decent restaurants and coffee shops, and a very relaxing vibe. It’s a place to unwind, and unwind we did.

The journey continued eastward as we cut our way between beautifully forested mountains and the roaring ocean, stopping in at lovely hamlets like Lorne and Anglesea. A big waterfall named Erskine Falls near Lorne was impressive, although packed with tourists. The Split Point Lighthouse near Aireys Inlet was similar. Closer to Torquay, we set off on the highly-recommended Koorie Cultural Walk, a 2km bushwalk dotted with signposted stories of the Aboriginal people of the region. A little further up the coast, we visited the legendary Bells Beach, home to a powerful point break (where waves hit a point of land jutting out from the coastline; vs. a beach or reef break) and host of Australia’s premier international surfing event since 1973, now called the Rip Curl Pro.

We spent a night in Torquay, one of the bigger towns on the Great Ocean Road. It was here, in 1969, that two surfer dudes started a company making surf boards and stitching together wetsuits. In choosing a name, one of the co-founders has said, “Ripping was groovy; surfing the curl was groovy; we wanted to be groovy – so that was it”. Rip Curl continues its groovy mission to this day. Also in Torquay, and in the same year, another two surfer dudes founded the surfing apparel brand Quiksilver, the powerhouse of boardshorts. Two of the big-three surfing brands in one town! Clearly, Torquay is the home of Australian surfing, and so its not really that surprising that it also hosts the one-of-a-kind Australian National Surfing Museum. Ella and I popped in to learn something about the sport. Apparently, modern surfing traces its roots to Hawaii, going back well over a thousand years. Hawaiians later taught the Californians the art of wave-riding, and the Californians went on to teach the world. I found the stories of key innovations that meaningfully changed surfing over time to be super interesting, including simple things like adding fins, to using polyurethane foam and fibreglass, or adding a third trailing central fin in the “Thruster” board design. With each new iteration, the sport gradually morphed into the fast-paced and nimble craft it is today. Overall, it’s an excellent museum that is well worth a visit. Nearby, all the surfing brands you can think of have put up large-format stores, which saw plenty of foot traffic that day.

We ended up having Christmas dinner that evening in a pretty smart Torquay resort, toasting a good year. The next morning, we carried on up the coast to Queenscliff, a little town with old-style architecture and glorious views across Port Phillip Bay and its heads. We popped into the quirky Queenscliffe Maritime Museum, which grew up and around its most prized possession, the very last Queenscliffe lifeboat, a Watson-class vessel that was built in 1925 and operated in nearby waters for 50 years. The museum’s collection spans all sorts of weird and wonderful maritime stuff, from charts and models to equipment and shipwreck salvage. Getting through “The Rip”, the entrance to Port Phillip Bay (3km wide, but shallow reefs limit the passage to about 800m) was notoriously treacherous in the early days, resulting in many a shipwreck. Even today, for larger vessels, regulations require that a specially licensed pilot board and steer the ship through the entrance.

We carried on further north, spending a day in the big city of Geelong, where we found some good coffee, nice fish & chips by a pleasant seaside promenade, and the surprisingly cool National Wool Museum. The museum essentially showcases the importance of the wool industry in shaping the city and the country. Sheep would have been amongst the very first European arrivals, and the native grassland provided a bountiful pasture. From 1820, wool became Australia’s largest export (shipping to London for “colonial auctions”), and remained so for 150 years. By the mid-1950’s, almost half of Geelong’s population was employed in the broader textile industry. Today, sheep still outnumber people three-to-one in the land Down Under. The museum building itself, in the heart of Geelong, is an old woolstore that was purpose-built in 1872, allowing for the storing, inspecting, and marketing of wool all under one roof. One impressive item in the museum is a massive and functioning carpet loom originally built in 1910. Holding eight different colours at a time, this complex machine uses a novel punched card system to automate the weaving of chosen patterns – effectively a type of early computer.

For our last night, we decided to detour inland to the city of Ballarat (pop: 113,000). It was here in 1851 that the state’s rich bounty of gold was first discovered, sparking the Victorian Gold Rush. Overnight, Ballarat became a boomtown, and people began arriving from all over the world in search of riches. Owing to the area’s unusually large and high-yielding gold deposits, the good times rolled on for nearly five decades, before things began to wane. Luckily, one is able to turn back the clock and explore 1850’s Ballarat at the city’s huge open-air museum called Sovereign Hill. It’s very well designed with a lot of attention to detail. Staff, fully kitted-out in the dress of the day, run regular little tours, shows, or events here and there. We managed to pan for gold (successfully), explore an underground mine, smash some old-time boiled sweets, and take in a show at the theatre.

A hop onto the highway, and we were back in Melbourne in a flash for our final few days of vacation.